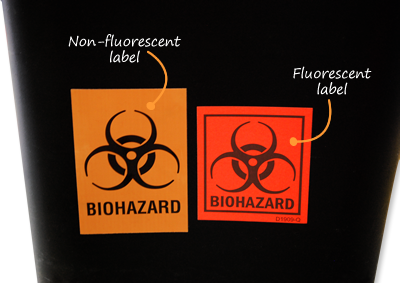

See the two labels above. It’s tough to really display, on a computer monitor, how much brighter fluorescent labels appear in when seen in reality. But, trust us! Fluorescent labels are bright and get attention.

See the two labels above. It’s tough to really display, on a computer monitor, how much brighter fluorescent labels appear in when seen in reality. But, trust us! Fluorescent labels are bright and get attention.

| Toxic: A chemical falling within any of the following categories: (a) A chemical that has a median lethal dose (LD50) of more than 50 milligrams per kilogram but not more than 500 milligrams per kilogram of body weight when administered orally to albino rats weighing between 200 and 300 grams each; (b) A chemical that has a median lethal dose (LD50) of more than 200 milligrams per kilogram, but not more than 1,000 milligrams per kilogram of body weight when administered by continuous contact for 24 hours (or less if death occurs within 24 hours) with the bare skin of albino rabbits weighing between two and three kilograms each; (c) A chemical that has a median lethal concentration (LC50) in air of more than 200 parts per million, but not more than 2,000 parts per million by volume of gas or vapor, or more than two milligrams per liter, but not more than 20 milligrams per liter of mist, fume, or dust, when administered by continuous inhalation for one hour (or less if death occurs within one hour) to albino rats weighing between 200 and 300 grams each. | |

| Highly Toxic (Poison): A chemical falling within any of the following categories: (a) A chemical that has a median lethal dose (LD50) of 50 milligrams or less per kilogram of body weight when administered orally to albino rats weighing between 200 and 300 grams each. (b) A chemical that has a median lethal dose (LD50) of 200 milligrams or less per kilogram of body weight when administered by continuous contact for 24 hours (or less if death occurs within 24 hours) with the bare skin of albino rabbits weighing between two and three kilograms each. (c) A chemical that has a median lethal concentration (LC50) in air of 200 parts per million by volume or less of gas or vapor, or 2 milligrams per liter or less of mist, fume, or dust, when administered by continuous inhalation for one hour (or less if death occurs within one hour) to albino rats weighing between 200 and 300 grams each. | |

| Reproductive Toxin: Chemicals which affect the reproductive capabilities including chromosomal damage (mutations) and effects on fetuses (teratogenesis) | |

| Irritant: A chemical, which is not corrosive, but which causes a reversible inflammatory effect on living tissue by chemical action at the site of contact. A chemical is a skin irritant if, when tested on the intact skin of albino rabbits by the methods of 16 CFR 1500.41 for four hours exposure or by other appropriate techniques, results in an empirical score of five or more. A chemical is an eye irritant if so determined under the procedure listed in 16 CFR 1500.42 or other appropriate techniques. | |

| Corrosive: A chemical that causes visible destruction of, or irreversible alterations in, living tissue by chemical action at the site of contact. For example, a chemical is considered to be corrosive if, when tested on the intact skin of albino rabbits by the method described by the U.S. Department of Transportation in appendix A to 49 CFR part 173, destroys or changes irreversibly the structure of the tissue at the site of contact following an exposure period of four hours. This term shall not refer to action on inanimate surfaces. | |

| Sensitizer: A chemical that causes a substantial proportion of exposed people or animals to develop an allergic reaction in normal tissue after repeated exposure to the chemical. | |

| Carcinogen: A chemical is considered to be a carcinogen if: (a) It has been evaluated by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), and found to be a carcinogen or potential carcinogen; or (b) It is listed as a carcinogen or potential carcinogen in the Annual Report on Carcinogens published by the National Toxicology Program (NTP) (latest edition); or, (c) It is regulated by OSHA as a carcinogen. |

| Inhalation: Chemicals may be inhaled into the lungs and then released into the bloodstream. | |

| Ingestion: Chemicals may invade the bloodstream after ingestion if it is absorbed through the small intestine, stomach, and the other sections of the digestive system. | |

| Skin Absorption: Chemicals may absorb chemicals on contact. | |

| Eye or Skin Contact: Chemicals on contact may affect the skin or eye. |

The following is categorized into the target organ effects that may occur in the presence of specific chemicals. It also includes examples of those specific chemicals as well as some of the signs and symptoms that may come about. The examples below show the various hazards possible in the work place and are made to help employers see the danger involved in these chemicals.

| Chemical | Effect on Body | Signs and Symptoms | Chemicals |

| Hepatotoxins | Chemicals which produce liver damage | Jaundice; liver enlargement | Carbon tetrachloride; nitrosamines |

| Nephrotoxins | Chemicals which produce kidney damage | Edema; proteinuria | Halogenated hydrocarbons; uranium |

| Neurotoxins | Chemicals which produce their primary toxic effects on the nervous system | Narcosis; behavioral changes; decrease in motor functions | Mercury; carbon disulfide |

| Agents which act on the blood or hematopoietic system | Chemicals which decrease your hemoglobin function or deprive the body tissues of oxygen | Cyanosis; loss of consciousness | Carbon monoxide; cyanides |

| Agents which damage the lung | Chemicals which irritate or damage pulmonary tissue | Cough; tightness in chest; shortness of breath | Silica; asbestos |

| Reproductive toxins | Chemicals which affect the reproductive capabilities including chromosomal damage (mutations) and effects on fetuses (teratogenesis) | Birth defects; sterility | Lead; DBCP |

| Cutaneous hazards | Chemicals which affect the dermal layer of the body | Defatting of the skin; rashes; irritation | Ketones; chlorinated compounds |

| Eye hazards | Chemicals which affect the eye or visual capacity | Conjunctivitis; corneal damage | Organic solvents; acids |

Locate section 8 n your 16-part MSDS. See the recommendations here and use these choices when you click on the Personal Protective Equipment ["PPE"] options shown on the custom RTK label Wizard.

| Eyes: | Use safety "Glasses" when presented with substances that cause mild irritation to the eyes. | |

| Use "Goggles" for liquid or solid substances that irritate, severely irritate or corrode the eyes as well as for gases that are able to cause frostbite. | ||

| Face: | Use a "Face Shield" for 'corrosive' materials. | |

| Hand: | It is recommended that "Gloves" be worn at all times. However, one must be aware of using the correct type of glove with specific substances. | |

| Body & Feet: | Use a "Full Suit" for "corrosive" materials that are "toxic" or "highly toxic" to the organs if one is exposed for too long. | |

| Use an "apron" should a full suit be unavailable. | ||

| Respirator: | Consult Section 8 of 6-part MSDS. • When using a respirator, one must judge the potential exposure level and use the appropriate respirator for each level. |